Re-Posted from the Conversation: Don’t despair if your teen wants to major in history instead of science

Historians’ work looks like meaningful disagreements around how to grapple with an ambiguous, complicated past. Here, ‘Pi’ sculpture by Evan Grant Penny, Wellington St., Toronto. (Brendan Lynch/Flickr), CC BY-NC license)

Historians’ work looks like meaningful disagreements around how to grapple with an ambiguous, complicated past. Here, ‘Pi’ sculpture by Evan Grant Penny, Wellington St., Toronto. (Brendan Lynch/Flickr), CC BY-NC license)![]()

Ian Milligan, University of Waterloo

It might be your worst nightmare. Your child, sitting at the kitchen table, slides you a brochure from the local university.

“I’ve been thinking of majoring in history.”

Before you panic and begin calling the nearest computer science department, or worse, begin to crack those tired barista jokes, hear me out. This might just be the thing that your child, and our society, needs.

Choosing to become a history major is a future-friendly investment. A history degree teaches skills that are in short supply today: the ability to interpret context, and — crucially — where we’ve been, so as to better understand the world around us today and tomorrow.

We’ve never needed knowledge of history and the skills that come with the discipline more than we do now. Not only is it a good choice of a major for all the usual selfish reasons — you’ll likely get a good job, even if it takes a bit longer than the STEM disciplines, and more importantly you’ll probably be very happy with it.

But for our society more generally, we need a generation with deep capacities to acknowledge context and ambiguity. This idea of ambiguity not only pertains to interpreting the past based on a diverse body of incomplete sources, voices and outcomes, but also how our contemporary judgements of that record shape our choices today.

Our whole society hurts when students turn their back on history. A sense of history — where we have come from, the shared anchors of democratic society, the why and how of our current moment in time — is critical.

Not enough historians

“Won’t you be lonely as a history major?”

When you’re visiting a campus library, take a look: you’ll see a lot of students reading their engineering notes, maybe some doing computer science exercises, even some English literature or political science essays being written. What you won’t see is many students flipping through their history books.

That’s because there aren’t all that many history majors left in many North American universities: York University has gone from 1,217 majors in 2011-12 to 527 seven years later; at the University of Waterloo, where I teach, we’ve gone from 227 to 89.

This is part of the broader decline in history majors which has seen enrolments essentially crash.

Why? On the face of it, it’s surprising that students who play Assassin’s Creed, listen to historical podcasts and watch historically themed television have turned their backs on the history major.

There are three reasons. First, education and law have seen tightening labour markets and falling applications. Traditionally history was seen as a good preparation for being a teacher or a lawyer. Second, there’s the overall “crisis of the humanities,” where STEM is seen as leaving liberal arts behind within universities more generally.

But also, historians (and their university departments) simply haven’t made the case for why history matters.

We stress critical thinking and writing — which, sure, a history degree does get — but often fail to get to the heart of why a history degree just might be the best training for the 21st century.

Macdonald analysis

“History? Is that so you can learn how to write?”

You can certainly learn how to write in history. But you can do that in any other arts discipline, and they’ll also teach you similar critical thinking skills.

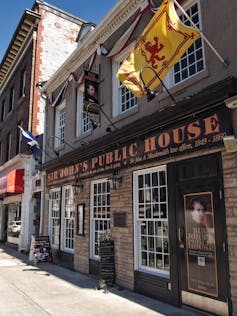

Historians can put these skills to work to understand our world today. Take John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister. The question for historians is not simply how he should be judged and commemorated today, but also how he should be understood within the context of his time.

In the 1990s, historians such as Timothy A. Stanley debated Macdonald’s legacy, pointing out the inherent racism of the 1885 Chinese Immigration Act; others such as Jack Granatstein lamented that students were likely to learn more about Louis Riel than Macdonald himself, despite, in Granatstein’s view, the latter’s accomplishments being “more important and much longer lasting.”

But those in wider society began to truly grapple with Macdonald’s legacy only in the last five or so years.

Forced reconsideration

The 2014 publication of James Daschuk’s Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Indigenous Life, convincingly argued that Macdonald used a deliberate policy of starvation to help “clear the plains” of Indigenous people.

This book, along with the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report, forced a reconsideration of how historians and society should teach or commemorate Macdonald today.

In some cases, municipal governments have removed statues (as in Victoria), or fostered ongoing conversations with Indigenous communities (as in Kingston, Ont.).

Historians and their arguments have been at the heart of these debates over Macdonald’s legacy.

In historians’ professional disagreements we can see the importance of history at work: it looks like meaningful disagreements around how to grapple with an ambiguous, complicated past.

Debate that stripped name

In 2018 there was a debate within the Canadian Historical Association that resulted in stripping Macdonald’s name from its long-standing best scholarly book award.

On the one hand, some historians saw the honour bestowed on Macdonald’s legacy by naming the highest prize as inappropriate given Macdonald’s record; others, highlighting Macdonald’s nation-building role, opted to vote in favour of keeping the prize name as it was.

Same historical record, different judgements. The ultimate vote was to — correctly, in my view — strip the name from the prize.

The weighing of historical context and grappling with ambiguity, on display during the Macdonald debate but even more so everyday within classrooms across the country, lie at the heart of what makes history as a discipline special.

Change the world through history

“I’m still not convinced. Why does what happened in the past matter for today?”

Historians don’t study history so they can know the future. Yet knowing where our society has been — and how to grapple with ambiguity and context — means that a historian is well equipped to interpret the world around us and where it might be going.

Put down the science brochures. If your high schooler really wants to be a history major, don’t panic. Smile, knowing that they’re taking the first step to a deeper understanding of the world around them.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]

Ian Milligan, Associate Professor of History, University of Waterloo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.